CLIFTON, SOUTH CAROLINA: A RIVER RUNS THROUGH IT

Mill race and shoals at site of former Clifton Mill 2. The tower glimpsed between the trees is all that remains of the mill, which was demolished in 2012

When I tire of commuting on the interstate, my alternate route between Traveler's Joy* and the university leads me past the imposing ruins of the Converse textile mill. When I began researching the role played in the Carolinas' history by textile mills and mill workers (see my previous post, "The Girl at the Window,") I realized that I lived surrounded by abandoned mills, with Converse being the last of three mills constructed on the rushing Pacolet River from 1880 to 1896 by transplanted Vermonter, Dexter Edgar Converse. I recently set out to find Clifton, the name given to the two mill villages built downstream of Converse where 'operatives' were housed who worked in Clifton mills #1 and 2.

Abandoned home in Clifton

In asking about the town, I had been surprised to hear from people who have lived in Tomahawk County* their entire lives that they have never visited.

Initially I found that remarkable, considering how close the settlement is to Traveler's Joy and even closer to the county seat.

But once I discovered Clifton, making my way up from the shoals where the mills once stood, navigating streets where ruined mill homes cling to the steep, spring-fed slopes, it became clear to me why it is not a destination for most people.

The streets of Clifton are quiet

There is a palpable sense of desolation in this river canyon, with only about one in four of the homes occupied and a few whose porches are so heaped with old furniture and debris that it is impossible to tell if they house living inhabitants.

Almost no one was about on the winter's day of my exploration.

On the steps of one crumbling house perched high above the river-road a pajama-clad girl sat dangling her bare feet over the abyss, absorbed in the image on her smart-phone.

At the tiny post office where I pulled in to read my maps, an elderly woman passed my car clutching her pocketbook and went into the building.

A few minutes later, no more enlightened about my route, I looked up to see the woman stationed at the post office window, regarding me with deep suspicion.

A heron fishes in the mill pond

Clifton's story is shared by nearly all the American mill towns abandoned by the textile industry in the last fifty years: automation rendering workers obsolete and capital seeking the kind of profit margins only possible where labor is dirt-cheap and regulations minimal. Southern textile mills held on longer than northern ones despite the fact that from the earliest days of mill-building in the Piedmont poor whites lured off tenant farms or carried down to the new mill towns from poverty-stricken hollows in the mountains consistently earned far less than their northern counterparts, as much as 40% less by some estimates. The argument was often made by the textile industry that the southeast's lower cost of living justified lower wages. However, as the authors point out in

Like a Family; the Making of a Southern Cotton Mill World

, the low cost of southern labor gave the products of southern mills a competitive edge in the market, "and mill owners, rather than workers, reaped the rewards." In the latter days of the 19th century and up until the depression in textile prices in the 1920s, "It was not unusual for mills... to make 30 per cent to 75 percent profit" (Hall 81).

The conspicuous inequity of such a system was brought home vividly to me while participating in the 2010 National Endowment for the Humanities Seminar on the growth of southern textile mills. That summer I visited the Victorian manor built by the Holt family, in Alamance County, North Carolina. The Holts presided over a textile dynasty beginning at the end of the Civil War and continuing until the close of the 20th century. In an upstairs bedroom the curator showed my fellow educators and me custom-designed apparel worn by a Holt heiress from a bygone generation, displaying the massive steamer trunk that accompanied the debutante and her wardrobe on annual crossings to Europe via luxury ocean liner. I remember trying to calculate how much labor those ocean crossings represented on the part of the twelve-year olds who toiled in the spinning rooms of the Holt family's Burlington mills. It was too oppressive an exercise to pursue.

In 1900 the average operative in a Carolina textile mill worked 12 hours a day, 6 days a week, with pay ranging from as little as 40 cents per day for doffers (bobbin-changers who were mostly young children) to as much as 2.50 per day for a weave boss (weavers were the most skilled of the mill workers, and the boss was nearly always a man) (Hall 79). Children worked the same hours as their parents, and in fact, housing in the towns was allocated based on the head of household contracting the majority of his family members to the mill. A visitor to Clifton in 1887 observed children as young as five working in the mills there; some were being paid as little as 15 cents a day (Teter 73).

And yet, it has been pointed out by many historians that at least in the earliest decades of the southeastern textile industry's phenomenal growth the majority of workers resisted efforts by organized labor and progressive political movements to regulate child labor and limit working hours in the mills.

Mill windows were boarded up in the 1970s when air conditioning was brought in

Fully recognizing, as 'lintheads,' that they occupied the lowest rung on the social ladder for southern whites, mill workers viewed efforts on their behalf by urban progressives as patronizing do-gooding that only hampered the ability of their families to earn living wages. To a great degree they were correct in this. As reported in

Textile Town

, a compendium of primary source accounts and historical perspectives on upstate mills published by Hub City Press in Spartanburg, reform efforts that resulted in legislation often drew down punitive measures against the mill workers by their employers. Typically, owners moved to charge rents on previously free housing or added new fees and charges to workers' paychecks in response to legislated improvements in their working conditions. Some took measures to quell dissent entirely. After the South Carolina legislature passed a bill in 1893 mandating that the maximum hours of a shift be reduced from 16 to 11 hours, most upstate mill owners resisted the law and some worked actively to undermine its effectiveness (Racine 53). In 1900 John Montgomery, the founder of Pacolet Manufacturing, and Seth Milliken, a Yankee potato farmer turned textile broker turned mill investor, bought a textile mill outside Charleston that was staffed entirely with black operatives.

One of two businesses in Clifton

Before the Vesta Mill opened, white operatives in the state had successfully resisted attempts to bring blacks into the mills to work alongside them, an exclusion that was formalized into law in South Carolina in 1915; black workers were only permitted to hold 'outside' jobs that mostly involved strenuous manual labor, like loading shipments or opening bales of cotton. With the low-country mill employing blacks in all its manufacturing processes, Milliken and Montgomery sent a powerfully threatening message to the white doffers, weavers, loom fixers and spinners in their upstate mills that they were entirely expendable. All active labor-organizing efforts ceased among upstate mill workers at that point, not to be resumed for thirty-five years. Meanwhile, Montgomery and Milliken quietly closed Vesta after one year. The black clergymen in Charleston who had been asked by the mill owners to recruit African Americans as textile operatives expressed dismay at the failure of this venture, accusing the investors of paying the workers so poorly it was no surprise that so many left their posts at the mill to harvest oysters, where they earned twice as much (Doyle 309).

The Converse mill, Clifton 3

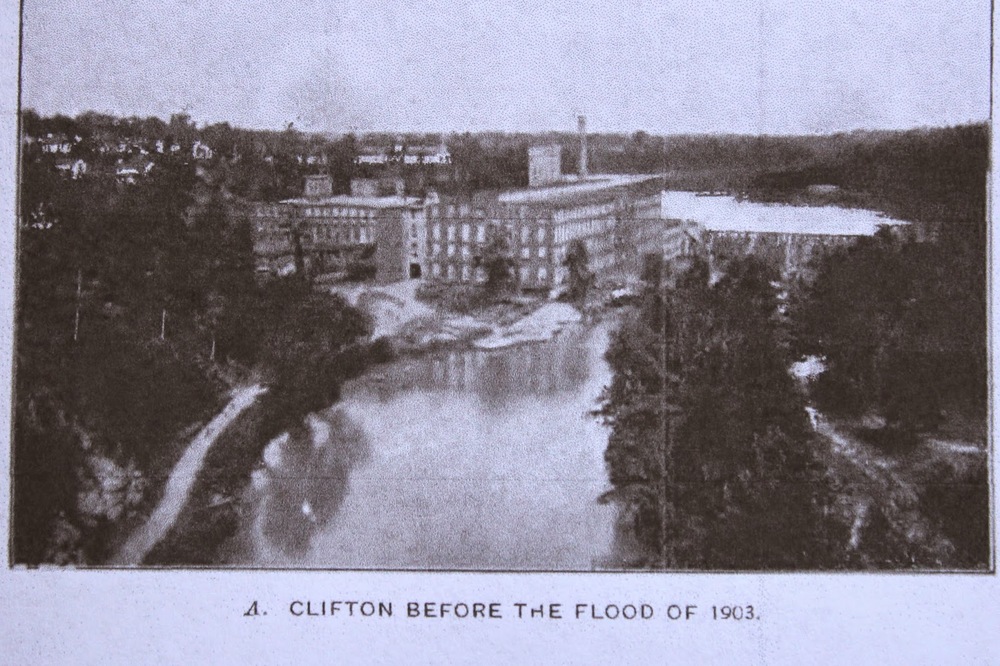

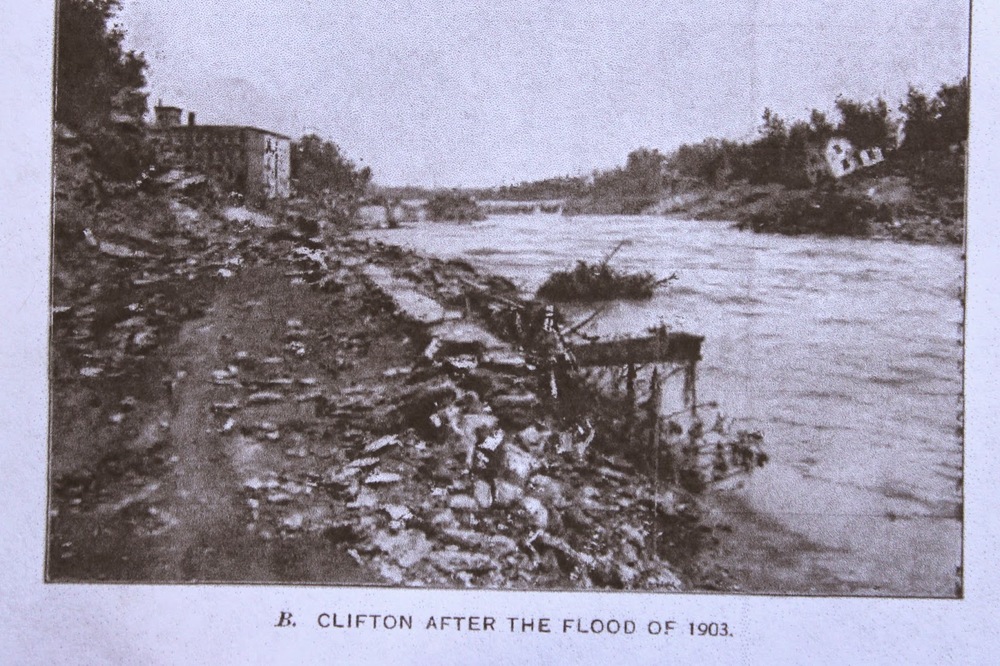

Clifton's rise and fall reflects some of this turbulent timeline, with distinctive differences. Economic disaster has been devastating to many former mill-towns, but Clifton's history was written by natural disaster, as well. The five-story brick edifice that still stands at Converse, turning its shuttered face to Highway 29 and to the railroad trestle that spans the Pacolet, is the second mill built at that site. So, too, was Clifton Mill 1 that stood less than a mile downstream on Hurricane Shoals until it was demolished in 2002, as well Clifton Mill 2, also known as the Dexter Mill, that occupied a commanding spot on an apron of land opposite Clifton Beach as recently as 2012. All three of these mills, along with the large mill nine miles further downstream at Pacolet, were swept away in the catastrophic flood of 1903, when an unlikely confluence of weather systems over the Pacolet Valley dropped what was estimated by the U.S. Geological Survey to be as much as 11 inches of water during the night of June 5th into June 6th.

A view downstream at the site where Clifton Mill 1 once stood. The steep angle of this canyon contributed to the flood's destructive power.

Beginning in the darkness before dawn, word began to go out that the river was rising rapidly, but no one had cause for serious alarm until the head machinist at the Converse mill found the wheel-room and boiler rooms flooded and was forced to stop salvaging materials when the water rose too quickly. Witnesses describe a wall of water 40 to 50 feet high sweeping down the canyon, an event corroborated by the New York Times' report on the flood which described the second floor of the mill as being flooded to four feet. "The Converse mill is utterly demolished", the Times announced on the morning of June 7, "nothing standing except the picker room building..." ("Cloudburst Sweeps Towns") Most of the mill building, the machine shop, the smokestack, the dam and over a dozen village cottages were washed downstream.

Not far down the river at Clifton Mill 1 workers were already assembling at 6:00 a.m. to file into work, although many were unsettled by the fact that the river was rising visibly, one foot every five minutes. Minutes later people sprinted for higher ground as debris from the Converse mill roared into sight ahead of a tidal wave of water surging atop the riverbed. It engulfed the Clifton Mill and swept away most of the structure, the equipment, and everything standing within 100 feet of the river. The force of the water was intensified by the unfortunate topography at this bend in the river, where a steep ridge rises abruptly from the canyon floor, presenting its face at right angles to the approaching channel. The effect would have been to concentrate the destructive force and velocity of the water as it roared towards the Dexter Mill and the lower Clifton village.

A night watchman at the lower mill who had been observing the rising water levels claimed to have spread the alarm that morning, warning mill workers about the impending flood. It will never be known why so many of the Clifton 2 villagers decided not to heed the warning and remain in their cottages, which were clustered directly below the mill on the river's left bank in an area known as Santuc. That is where loss of life was greatest, with 52 people swept to their deaths, most of them women and children. Survivors were plucked from roofs and trees, but more than one Clifton resident was spotted riding the flood for miles before disappearing in the torrent at the broken dam at Pacolet, where the level of destruction was also profound. In all, 65 people drowned in the villages of Converse, Clifton and Pacolet, including infants, newlyweds, and one entire family numbering eleven members.

(Photos courtesy of U.S. Geological Survey of the Dept. of the Interior: "Destructive Floods in the

U.S. in 1903," published in 1904.

Once the flood subsided, bodies had to be fished from the river, disentangled from machines and building remnants, or dug up from the mountain of silt that covered the former site of Santuc. Those who survived were without work. Relief was slow to reach the towns, so much so that journalists criticized the inadequate response of those mill owners who were in charge of funds donated by the public for flood survivors, saying they seemed unable to grasp the fact that residents of the devastated villages lacked adequate food, shelter and medical care for days after the disaster. (Sound familiar?...like a certain hurricane that struck our Gulf shore 100 years later?)

Standing on the right bank of the Pacolet on this sunny morning in 2015, I watch a blue heron fishing on the rim of the Dexter mill race and try to imagine the mill that once stood here. I try to see it filled with the people who tended the looms, stripped cards, and ran sides in the spinning room through the deafening clatter of machines and the stifling air, thick with cotton dust. 4,000 people once lived and worked in Clifton. Where did they all go? What did they leave behind? What is worth salvaging? How does a community move on in a way that honors tragedy and toil but isn't stifled by it? How can people be convinced to stop resisting change out of habit, and forfeiting opportunity out of inertia?

Bridge over Lawson's Fork at Glendale, SC -- the mill stood on the right bank

The answers to those questions may lie a few miles south of Clifton in the former mill town of Glendale. Glendale sits astride Lawson's Fork Creek, a tributary of the Pacolet. (The town was initially named Bivingsville, but was changed after mill owner Dexter Converse's wife Nellie returned suitably impressed from a trip to Southern California.) It was spared the devastation experienced by its neighbors to the north, although the mill dam was washed away in the 1903 flood, along with the trolley line and several warehouses filled with cotton.

Glendale water tower

Being somewhat closer to Spartanburg, modern-day Glendale may benefit from the progressive influences of a modern urban center in close proximity, but it has also capitalized on that connection through civic initiative. The 20-acre Glendale Shoals Preserve is managed jointly by Wofford College, Palmetto Conservation Foundation, and Spartanburg Area Conservancy on the site of the former mill, with Wofford's Goodall Center for Environmental Studies housed in the mill's former office, now restored. (The rest of the mill burned down in 2004.)

Entrance to the Carolyn Converse Garden at the Wofford Environmental

Studies Center in Glendale

Whereas Clifton was deserted on the sunny Saturday morning I spent there, the shoals below the Wofford E.S. Center were thick with day-trippers: families walking their dogs, visiting the Carolyn Converse Garden adjacent to the Center and snapping photos of the dam and the picturesque mill-tower which juts above the verdant landscape like a campanile in an Italian Renaissance painting. In warm weather the roaring creek attracts kayakers. Environmental writers have convened here for conferences in summers past. Wofford students come out regularly from the college in town to take classes at the center and study habitats among the shoals.

Steve Patton tends the garden on the Glendale mill site

In exploring the garden, my husband and I stopped to chat with Steven Patton as he was pruning grapevines. Mr. Patton is a Glendale resident who, with the help of Wofford students, tends the native vineyard as well as the pollinator beds, medicinal herb plants and assorted fruits and vegetables in the CCG. (He also fields questions from interested strangers in an unflappably friendly manner.)

Of the nine varieties of muscadines and scuppernongs growing on the Glendale site, he's most fond of 'Scarlet' muscadine for its intensely sweet flavor, and 'Magnolia,' the bronze scuppernong, for its beautiful color, and invited us back in August to see the grapes in their glory. I promised to send him my recipe for muscadine wine.

Glendale shoals

Before leaving Glendale we explored along the crest of the hill that rises gradually from the post office, trying to find the antebellum house we could see from the shoals. We discovered it surrounded by chain link fencing, the windows boarded up with plywood and the proud columns obscured by weeds as tall as cornstalks. This was where D. E. Converse and his wife lived in the 1880s before they moved to a stylish neighborhood in Spartanburg to be among other textile tycoons. Old photographs depict it with flowerbeds, a child standing on the steps. The views from the west facade -- over the mill pond, the river, the brick mill and its towers -- must have been impressive back then. It's still very appealing, with the slanting winter light glancing off the river, lighting up the spreading oak that dominates the garden.

This countryside is thick with ghosts. But as the sun ebbs away and our car climbs out of the Pacolet Valley I remind myself that the only ghosts who ought to trouble us are the living ones.

####

The former home of mill tycoon Dexter E. Converse in Glendale, SC

To read more about the Goodall Center and follow links for Palmetto Conservation Foundation and Spartanburg Area Conservancy, go to:

www.wofford.edu/goodallcenter/

####

WORKS CITED

"Cloudburst Sweeps Towns; Thirty Killed."

New York Times Archives

. 7 June 1903. Web.

Doyle, Don H.

New Men, New Cities, New South

. Chapel Hill: the University of North Carolina Press, 1990. Print.

Hall, Jacquelyn Dowd and James Leloudis, Robert Korstad, Mary Murphy, Lu Ann Jones, Christopher B. Daly.

Like a Family; the Making of a Southern Cotton Mill World.

Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press, 1987. Print.

Murphy, E.C. "Destructive Floods in the United States in 1903."

U. S. Geological Survey of the Department of the Interior

. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1904. Web.

Racine, Philip. "Boom Time in Textile Town 1880 to 1909."

Textile Town

. Ed. Betsy Wakefield Teter. Spartanburg: Hub City Writers Project, 2002. 37-59. Print

Teter, Betsy Wakefield, ed.

Textile Town

. Spartanburg: Hub City Writers Project, 2002. Print.