THE MOUNTAINS ARE OUR MASTERS

Slowness is a luxury these days. Like silence, and letters, and

friendship. No one has time. We work and work because nothing is certain

anymore (and if we needed reminders of that, many of us got them with October’s

shutdown of the government). Having even

one day off in which to do a lot of nothing and to savor it slowly feels like serious

sin. And yet, summer isn’t intended for

workdays that stretch like doom from morning into deepest night.

The five fledgling wrens, the ones hatched in a dented bucket I hung from the eaves of the potting shed last spring, form a little mob that perches on the back gate in the mornings. As I’m rushing off to work thirty miles down the freeway, they’re clustered on the chain links, primping and chirping until Miss Billie is worked into a froth in her hiding place beneath the pumpkin vines. They’re trying to warn me that time is fleeting -- that it’s spent quickly and is gone.

The five fledgling wrens, the ones hatched in a dented bucket I hung from the eaves of the potting shed last spring, form a little mob that perches on the back gate in the mornings. As I’m rushing off to work thirty miles down the freeway, they’re clustered on the chain links, primping and chirping until Miss Billie is worked into a froth in her hiding place beneath the pumpkin vines. They’re trying to warn me that time is fleeting -- that it’s spent quickly and is gone.

Without

truly being able to spare the time, my husband and I heeded the wrens and stole

one day recently to drive to Asheville, to feast our eyes on those hypnotically blue, blue mountains that ring the city like a celestial crown. We needed to sit

at a sidewalk café on Battery Street watching people and dogs pass by while we

drank our coffees slowly and then slowly drank our refills while we

talked.

|

| Battery Street, Asheville, North Carolina |

We longed to spend an entire

afternoon in the company of books (yes, the slow kind, with paper pages

smelling of ink and revelations) so we headed down the street to Malaprop’s, our

favorite bookstore this side of San Francisco and the only establishment where

I am able to lay down large sums of cash without the slightest twinge of

self-reproach.

|

| Malaprop's Bookstore, Asheville |

|

| Wall Street, Asheville |

We’d been

prepped for this richly human pace by a stop we made on the way up the

mountainside, not far outside Hendersonville, North Carolina. Our destination

there was a beautiful valley shaped like a gravy-boat. It is rimmed with hemlock forests, clouds

balanced on the spout. As usually

happens when I coax my husband into one of these off-the-beaten path

explorations, he insists on using GPS and I insist that the only place the

prim-voiced Miss Magellan is sure to lead us into is an argument. I was right again. After guiding us out of the suburban

cul-de-sac where technology had mired us, I consulted the map (the slow way,

naturally) and we arrived at last at the historic Johnson Farm.

|

| Historic Johnson Farm, Hendersonville NC |

The

Victorian house is discovered after a short walk through the woods. Built over a ten-year period by a Mr. Moss,

who reportedly made the bricks from clay taken from the French Broad, it was

completed in 1880. By that time Mr. Moss

had been ruined, however, in the Depression of 1873 (it seems Wall Street has

been pulling the rug out from under hard-working Americans ever since there was a Wall Street) and was forced to

sell his dream home to a prosperous farming family, the Leveretts. Sallie Leverett grew up in the house, but

moved away to marry. When her husband

Leander Johnson died, she came home to the valley to live in the brick house

with her two sons, Leander Jr. and Vernon.

Like many widows of the time, Sallie put food on the table by taking in

boarders. The Blue Ridge mountains were

a popular summer destination for heat-stressed lowlanders even then, and

Sallie’s business grew so successful that she made the boys build a rooming

house next door to the brick farmhouse, with a broad porch for rocking and

eleven small rooms whose windows opened to the mountain air.

|

| Muscadines |

(The building

houses a weaver’s collective now, which keeps the rooms buzzing with the sociable

kind of productivity Sallie Johnson would most certainly have approved of.) With

three meals daily, ice cream and hay rides for the grand sum of $5 weekly, the

Johnsons had many repeat visitors. Mrs. Johnson

is described by people who knew her as being just as genial as her sons, but

one can’t help making comparisons to another boarding house operator from

roughly the same time: Eliza Gant, the fictional version of Thomas Wolfe’s mother

Julia and the crafty proprietor of ‘Dixieland,’ whose unflattering portrait features

in Wolfe’s novel, Look Homeward Angel. I have saved a postcard I bought years ago on

a tour of Julia Wolfe’s rooming house on Spruce Street, shortly before an

arsonist’s fire gutted it. It is a

photograph of Tom’s small bedroom on the second-floor sleeping porch. It shows the narrow iron bed and the windows

open to the treetops – a place simultaneously confining and emancipating, just

as Asheville (or ‘Altamont,’ as it’s called in the novel) proved to be for a

young writer driven into the wider world by an overwhelming appetite for life.

|

| The rooming house |

|

| The rocking chairs at the rooming house are situated to catch the breezes. |

After the

book was published in 1929, Wolfe was forced to stay away from his hometown for

eight years; the good citizens of Asheville, many of whom recognized themselves

in the descriptions of unsavory characters (“crude, kindly, ignorant and murderous people”(121)), did not easily

forgive their native son. Wolfe’s mother

bore the brunt of her son’s sharply critical eye. While the hero of

Wolfe’s autobiographical book, Eugene Gant, alternately adores and forgives his

hopelessly alcoholic father, he detests the mother he perceives as having sacrificed

her family to the more fulfilling practice of running a profitable business. “…in

Gant,” he writes, “there was a silent

horror of selling for money the bread of one’s table, the shelter of one’s

walls, to the guest, the stranger, the unknown friend from out the world; to

the sick, the weary, the lonely, the broken, the knave, the harlot, and the

fool” (132).

There is no

record of resentment on the part of Sallie Johnson’s sons, despite the fact

that they apparently worked tirelessly to keep the farm running and accommodated

themselves to the needs of their mother's business, to the extent that they neither married nor moved off the farm in their lifetimes. When the rooming house filled at the peak of

summer and the farmhouse was filled to the rafters, Sallie typically moved her

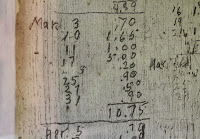

sons out to the chicken coop and put boarders in their beds. Long-suffering and ever practical, the young

men recorded rainfall totals on the side of the coop while camping out there, neat

columns of penciled sums which a visitor can still make out against the flaking

paint. Meanwhile, Vernon set to work

(when did he have a minute to spare?) building himself a snug cottage behind the

farmhouse that was finished in 1933, when the men were finally able to vacate

the coop.

|

| Writing on the coop |

Thomas Wolfe

left Asheville in 1916, enrolling at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and believing that he had put the small minds and vast peaks of his hometown behind

him. He longed to move in the rarefied

circles of the highly civilized, and yet he spent the rest of his short life purging

his natal landscape from his heart in great swathes of lyrical, emotionally

charged prose. (He died unexpectedly of tuberculosis of the brain at the age of

38; his sister Mabel, brother Fred, and yes – his mother – rushed out to

Baltimore to be with him at the end.)

It’s

possible that Vernon and Leander, in their decidedly uncelebrated

way, didn’t need to leave their beautiful gravy-boat valley in order to

comprehend what it took an artist like Thomas Wolfe years of demon-wrestling and miles of traveling

in distant places to express. They

bequeathed all their farmland to the Henderson County school district on their

deaths, and a middle school was built in the heart of the meadow that borders

the county road and the farmhouse beyond.

It’s impossible to know if either

one ever read the works of their countryman, but it’s not hard to imagine,

considering the gift of their own natal landscape to their region’s future

generations, that they would have appreciated better than most what the

narrator in Look Homeward, Angel meant

when he said of Eugene Gant that “the

mountains were his masters. They rimmed

in life. They were the cup of reality,

beyond growth, beyond struggle and death.

They were his absolute unity in the midst of eternal change.”

The Historic Johnson Farm is located at 3346 Haywood Road, Hendersonville, NC 28792. Guided tours are available on certain weekdays from 8:00 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. and festivals are held at the farm twice annually -- the Spring Festival on the last Saturday in April, and the Christmas Festival held the first Saturday of December. For more detailed information call 828-891-6585 or visit the website:

|

| Pearson's Falls, near Saluda, NC, in the Blue Ridge Mountains |

The Historic Johnson Farm is located at 3346 Haywood Road, Hendersonville, NC 28792. Guided tours are available on certain weekdays from 8:00 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. and festivals are held at the farm twice annually -- the Spring Festival on the last Saturday in April, and the Christmas Festival held the first Saturday of December. For more detailed information call 828-891-6585 or visit the website:

WORKS CITED

Wolfe, Thomas. Look Homeward, Angel; a Story of the Buried Life. Scribner 1929. New York.