TRAMPLING OUT THE VINTAGE; Making Wine While the Sun Shines

Dahlia 'Purple Powder Puff'

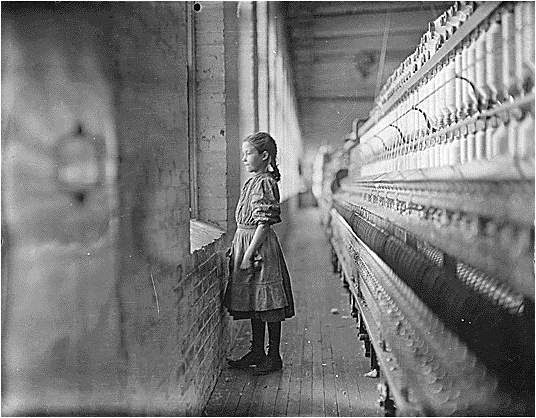

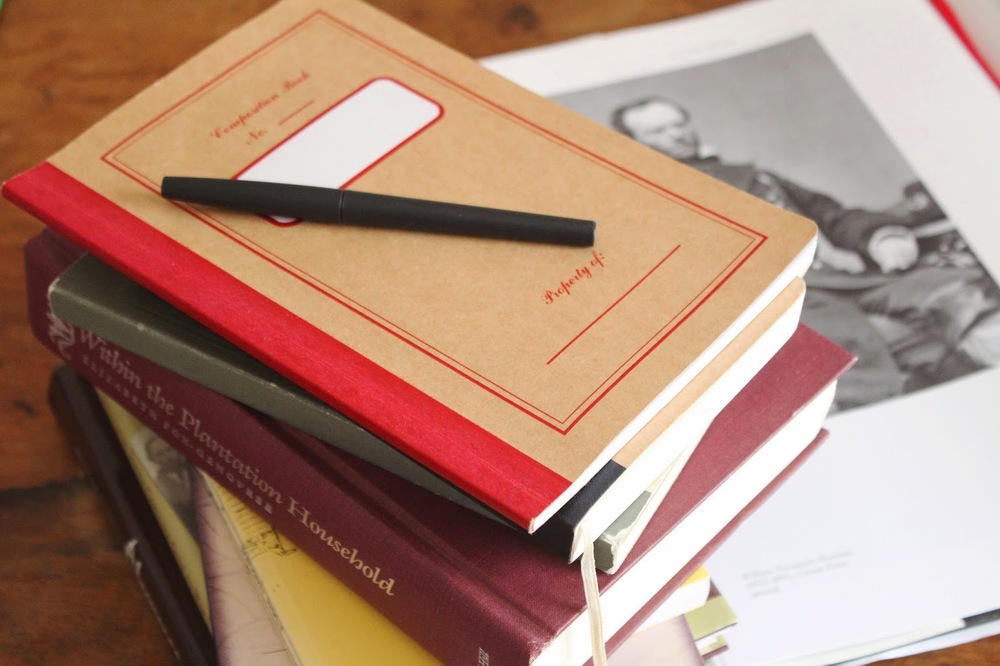

I started a new job recently, ending the old one more abruptly than I’d planned. I came out of my last afternoon class in the first week of the fall semester to find a message on my phone calling me to an interview. Dropping my books in the parking lot, I begged the department chair to hang on, telling him I would break all traffic limits getting to his office in a campus on the other side of town.

I signed the new contract at 5:00 p.m. and never set foot again in the college into which I’d been pouring my heart, my soul, and my terrible grammar jokes for the last five years.

Miss Billie drinks up

The situation at Tomahawk Community College* had become untenable in so many ways. The story of a top-heavy administration making decisions that consistently hurt students and undermine morale is pathetically ordinary; rather than bore folks with the details I now serve up my variation on the light-bulb joke. (How many academic vice-presidents does it take to change a light bulb? Answer: None. They’d much prefer students and faculty to be kept in the dark...)

While the learning-curve on a new job can be daunting, and this one certainly is, I’m so happy and grateful to have found deliverance in a functioning institution of higher education that I’m tackling all the new systems and curriculum head-on.

What can’t be avoided is giving all of one’s time to this process until the stage of mastery kicks in, and for now that means looking through the window at the garden while I grade papers on a Sunday afternoon rather than being out in the beds with the dahlias and Miss Billie.

I’m grateful for the three week break in August that allowed me to squeeze out two distinctive vintages before diving into the new semester: I managed to finish a second novel I’d begun in May which had claimed my attention to the exclusion of everything else, and my husband and I harvested muscadine grapes from the ‘Noble’ vine I planted on the vegetable-garden arbor three years ago, deciding that with such a stupendous crop we were obligated to make wine.

Late last winter I had dragged my old Master Gardener pruning diagrams out into the garden and cut the vine just as the notes advised.

I didn’t expect it to make much of a difference, but I became a pruning convert after seeing the vine covered in fat black fruit by summer’s end; the sweet smell of the grapes ripening in the heat could make you swoon if you stood too long at the gate.

Muscadine 'Noble'

Over the years of reading 19th century southern women’s journals I’ve come across entries referring to seasonal wine- and cider-making, but if recipes are included they are rarely adaptable. (“For every bushel of fruit, use a hogshead of sugar…”) The friendly staff at the Traveler’s Joy* Library helped me out in that respect.

In late summer I was spending a good deal of time at the library’s tiny History Room, a cubicle with collections of odd local lore and family history. It was here, while looking through volumes of coroner’s inquests from southern counties during and just after the Civil War, that I found the account of a young woman accused of murdering and burying an unwanted child, a young woman who gripped my imagination and refused to let go until I’d written her story.

On a break from researching, I mentioned to my library friends that I had a mind to try making wine from my muscadines. These three librarians appear to know every soul who currently lives and breathes in Traveler’s Joy and which one of these souls possess remarkable skills or attributes. All are familiar, by reputation, with a congregant of the Reformed Presbyterian Church who has a famous recipe for the stuff. His brew calls for cornmeal in the fermentation process, a southern influence if I ever saw one. My old neighbor Steve S. had given me a copy of the church’s cookbook, and there I found the recipe.

On a warm day FK and I plucked the grapes with the mockingbirds scolding – smart squatters that they are, this social-climbing couple built a stout nest deep in the arch of the vine.

After mashing the grapes to pulp in a roasting pan, we filled two 1-gallon plastic jugs with the fruit, peels and all. Over the fruit we poured the sugar syrup, and lastly, I lowered the cornmeal packets – one tablespoon of plain cornmeal wrapped in cheesecloth and tied with string, into each jug. The recipe calls for a ‘big, strong balloon’ to be placed over the mouth of the jug while it ferments, to allow the gas to build up without exploding the jug. I couldn’t find balloons big enough to fit over the jugs’ mouths, so we settled on the brilliant idea of affixing surgical gloves, instead. Jugs, fruit, gloves and all went on a shelf above the washing machine "someplace that stays warm and about the same temperature, for 3 to 4 weeks, or until the balloon stops filling."

Straining the mash

Four weeks later we took the jugs down, removed the balloons and the cornmeal sachets, poured the juice out carefully without stirring or shaking the fruit, and strained it into bottles. The color of the young wine is identical to the ‘Purple Powder Puff’ dahlias that are blooming in the garden now, and the taste isn’t half bad, if you like your liquor sweet.

Our batch filled five recycled whiskey bottles and went into the slant-back cupboard in the kitchen to age in darkness and tranquility.

Muscadine wine, ready for aging.

*****

Work in 2014 has taken on the dimensions of a valued but voracious animal: it consumes all the food and attention lavished on it and growls for more, threatening to leave the caretaker with nothing but the tending. We have no option but to work hard. However, we must hold out these little pieces of our natures that restore us to ourselves, that allow some minor tributary of the creative force to flow in our veins, lending flavor to homemade wine and encouraging us to turn forgotten lives into fiction.

I'll drink to that!